Our next featured scientist is Clare Flynn, a PhD candidate Department of Ecology and Evolution at the Stony Brook University.

About Clare

At one point, Clare Flynn never imagined herself going to Antarctica. During her internship studying seabirds for Project Puffin, when it was suggested studying seabirds could one day take her to Antarctica, she had joked “It’s so far, that’d be crazy!” But as her interest in birds grew, so did her adventurous spirit.

She enjoyed working with seabirds because they serve as a good indicator of ocean health and are often much easier to count than fish. They can be a lens to see beneath the surface. Her favorite seabird, the small Arctic tern, migrates from Maine to Antarctica (about a 30,000 km/19,000 mi round trip) every year in just a few weeks. It sees the most sunlight of any animal in the world.

Inspired by her interest in seabird statistics, Clare found a funded PhD program focused on counting penguins, and a previously unthinkable trip to Antarctica soon became her dream. Because her lab had worked with 60 South before, when they sought another guest scientist, she eagerly took the opportunity. In Northern Winter 2023 and 2024 (southern Summer!), she traveled to the Antarctic Peninsula, conducting research for her dissertation while sharing her knowledge with the passengers.

Research with 60 South

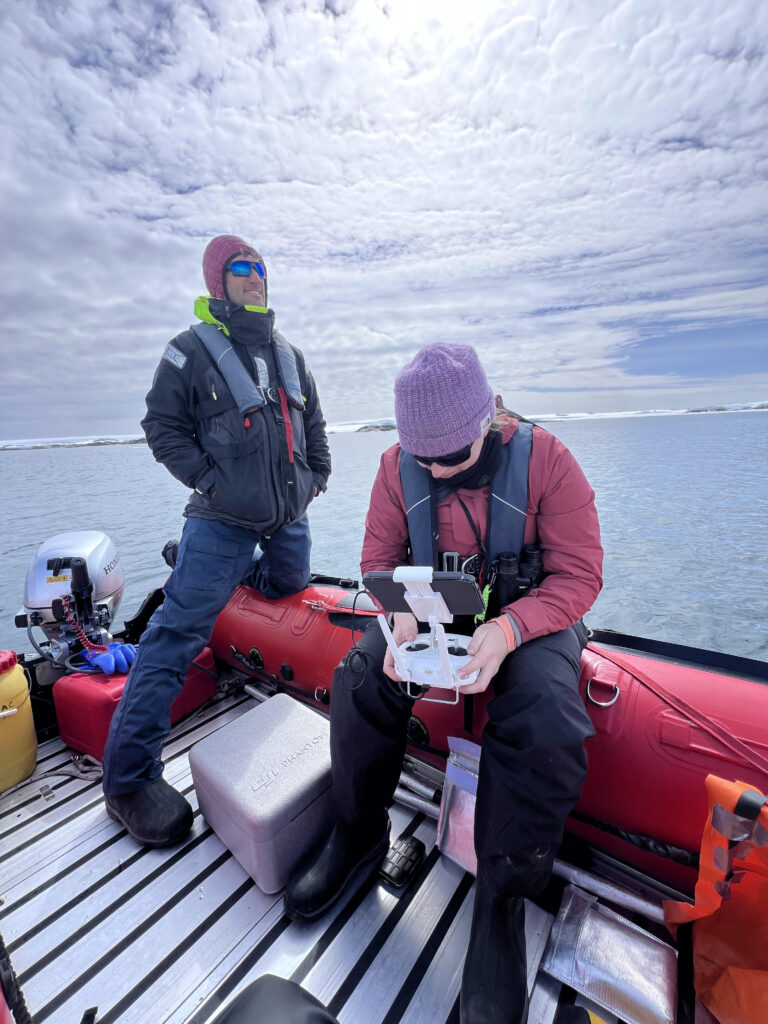

Clare counted penguins using clickers and drones to track changes in their populations, adding to the data collected since the 1970s. The numbers reveal that most penguin populations have declined in recent years, likely due to melting ice that disrupts their breeding needs and food supply. Penguins primarily consume krill, which nest under the ice to eat the algae growing there. Less ice would lead to fewer and smaller krill, thus endangering the penguins. However, the Gentoo species, which prefers warmer weather, bare rock, and a more varied diet, has expanded rapidly in a process jokingly called “Gentoofication.” But even the Gentoo face risks as the marine environment continues to destabilize.

For a penguin population database, Clare counted all three Pygoscelis penguin species on the Antarctic peninsula– the Gentoo, Chinstrap, and Adélie– but she is focusing on the decline of the Adélie for her PhD dissertation. She is trying to determine which section(s) of the penguin life cycle have most contributed to their population decline: adolescent survival, adult survival, breeding propensity (what percent of the population chooses to breed each year), or breeding success (how many offspring each individual has). She has already ruled out adult survival, since most penguins who reach maturity survive at the same rate each year as before, leaving the other three stages to explore.

She believes that one modern danger the Pygoscelis penguins face includes the increased precipitation on Antarctica, which threatens the survival of young penguin chicks. Once considered a ‘polar desert,’ Antarctica has seen increasing precipitation in recent years. During the critical months before penguins molt their downy feathers for adult waterproof coats, they risk becoming sick and dying from exposure to the cold, wet snowfall. However, the exact changes in precipitation and their effects are hard to measure due to Antarctica’s lack of weather stations and powerful winds, which cause precipitation to fall nearly sideways instead of directly into measuring devices, and could knock the devices over entirely.

Another theory explores the impact of tourism on penguin breeding. Studies of penguins’ heart rates revealed that humans’ noisy, abrupt movements caused them considerable stress, but slow and quiet approaches significantly reduced the impact. These findings motivated the IAATO’s 5 meter distance rule for visitors. Recent data suggests that penguins can acclimatize to humans, and greater disruptions are needed to generate the same level of stress. However, on hypothesis from Clare’s advisor suspects that rather than acclimating, perhaps the penguins most disturbed by human activity have left popular tourist spots, including Port Lockroy, while unaffected penguins remain.

All penguin population data is stored in MAPPPD, a platform many scientists use alongside data including ice levels, temperature, and krill fisheries to analyze the impact of environmental factors. Decades of data will help Clare refine her model for analyzing Adélie life cycles. Her dissertation will also include a list of sites for annual population counts to better track population changes over time.

Notable Memories

Clare loved the excited, adventurous spirit of the passengers and crew. They always wanted to help, whether watching the drone to avoid skuas that may try to swoop the drone while Clare was focused on the ground below, or catching it from the air after a scan. She also enjoyed giving presentations and watching them apply her teachings. By the end of the trip, they could accurately differentiate between the three penguin species on the peninsula and make their own observations, like noticing how penguins lay no more than two eggs at a time.

They even helped her consider new perspectives. When Clare wondered why Chinstrap and Gentoo penguins nested on a certain strip but not the Adélie, one passenger with geology knowledge suggested studying the fault lines, since Adélies require a particular type of rock to breed. On her first trip, the captain, Jarred, also recommended a site where he’d seen penguins for years, even though it wasn’t marked in the database.

She remembers hiking up to a beautiful vantage point of Paradise Bay after finishing her penguin counting early. While the bay had been packed with multiple cruise ships the day before, at that point it was completely empty. From the overlook, she watched whales raise their tails out of the water and 60 South passengers slowly kayaking around the point. The peace and beauty of the scene amazed her, a reminder that she could experience such incredible nature with a handful of others. On such a small ship, she had the chance to connect with everyone individually, and even plans to catch up with a few passengers if she travels for a conference near them in the future.

We love to hear about such meaningful connections and wish Clare the best of luck on her dissertation!